As most of you know, I’m Ayla, and for the past two and a half years I’ve been volunteering as a Nurse with Mercy Ships. For most of my time with Mercy Ships, I was serving on board the ship in the hospital as a nurse and I truly loved it. There is something incredibly special about providing direct patient care, seeing lives changed through surgery, and being part of such a unique community.

But from the very first time I stepped on this ship, way back in April 2023 and I heard about our Education, Training, and Advocacy team (ETA) I knew that was where my heart was pulled. I’ve always been passionate about development work, about creating change that lasts long after we leave. The idea of equipping and empowering local healthcare professionals to lead in their own hospitals and communities resonated deeply with me.

In hindsight, I can see that it wasn’t just passion, it was God’s calling. He was planting a seed long before I realized what He was preparing me for.

And then in January that dream became a reality and I stepped into a new role, working with ETA. This role now takes me off the ship and into Sierra Leone’s main teaching and referral hospital, Connaught, where I help run our Nurse Mentorship Program with my colleague and friend Katie.

I want to give you a glimpse into what it means to work alongside some of the most resourceful, resilient nurses I’ve ever met. You’ll hear about the realities of healthcare in Sierra Leone, not sugar-coated, but also not hopeless, because what I’ve seen here is not defined by limitations, but by possibility.

I want to share the vision and structure of our Nurse Mentorship Program, the changes we’re seeing, and the stories of nurses whose confidence, leadership, and clinical skills are growing every day. I’ll also share my own journey, how this work has challenged me, changed me, and deepened my belief that when you invest in people, transformation follows.

Context is Everything…

When I talk about Nurse Mentoring, I can’t just dive into what we do without first painting a picture of the place we do it in. it’s important to understand the setting in which it exists, because context changes everything. The needs here, the way care is delivered, and the way teams work together is different from what many of us have experienced elsewhere. And yet, that difference is also what makes the work so vital.

Sierra Leone is a country of about 8.4 million people, and its healthcare system is a patchwork of government-run hospitals, private clinics, and facilities supported by NGOs or faith-based organizations. The main referral and teaching hospital in the country is Connaught Hospital, right in the center of Freetown. It’s the place where patients with the most complex or urgent needs from all over the country are sent.

The history here has shaped the health system in profound ways. The civil war of the 1990s tore apart infrastructure and displaced countless healthcare workers. Then, just as the country was rebuilding, the Ebola outbreak hit. It not only claimed thousands of lives, but it took a heavy toll on the very people meant to protect public health, nurses, doctors, community health workers. And even today, the system continues to feel the ripple effects, shortages of trained staff, limited access to essential medicines, fragile supply chains.

To put into perspective staff shortages, I know some people love numbers. There is approximately 0.2 surgeons per 100,000 people. In contrast, Australia where I am from has approximately 22 surgeons per 100,000, a ratio 110 times higher than Sierra Leone’s, highlighting an enormous disparity in surgical workforce capacity.

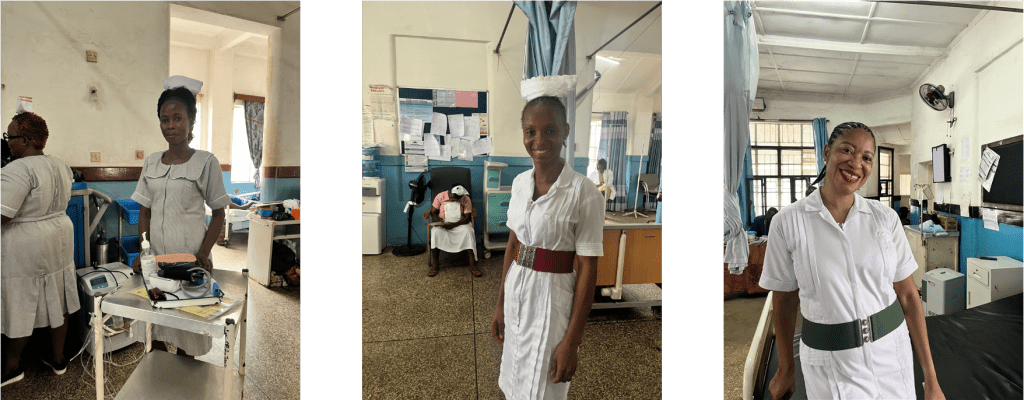

The Nurses

But I want to talk about the nurses because that’s who I train, mentor and work alongside every day. Nurses are the backbone of healthcare in Sierra Leone. They are the ones who keep the wards running day and night, often with little more than their own skill and determination. In Sierra Leone there are three main cadres of nurses.

First, there are the SECHNs, State Enrolled Community Health Nurses. This is a certificate-level course, and SECHNs form majority of the nursing workforce at Connaught Hospital. This course is no longer offered in Sierra Leone. The change I believe was part of a move towards higher levels of nursing education, with the aim of standardizing training and ensuring that all new nurses graduate with the skills and knowledge needed for increasingly complex healthcare environments.

While SECHNs are no longer being newly trained, those still working bring years, sometimes decades of experience. Today a lot of SECHNs are going back to school to upgrade their education which is exciting for the country.

Then there are the SRNs, State Registered Nurses, who have undergone longer training around 3 years – similar to a diploma for most of us back home.

Finally, there are the NO’s, Nursing Officers which is equivalent to a bachelor’s degree, however here in Sierra Leone the training is 5 years, NO’s often take on leadership and specialist roles. Each cadre has different levels of training and skills, and yet in practice, they work side by side, covering for one another in the same high-pressure environments. At Connaught on the wards I work at there is usually around 1 or 2 NOs per ward and then the rest of the nurses are either SRNs or SECHNs.

One of the realities that’s hard to grasp until you see it firsthand is that not every nurse in the hospital is actually being paid. There’s something here called the “pin code” system. In order to receive a government salary, a nurse must be “pin coded,” which is a formal registration and placement within the system. The process is long, bureaucratic, and there aren’t enough positions available. This means many nurses you see working long shifts in the wards are technically volunteers, they show up every day, care for their patients, and yet take home no salary. They do it because they feel a calling, because the need is great, and because they believe their work matters.

But for many, there is also no other choice, without a pin code, they cannot receive a salary, and the only way to be considered for one is to prove themselves through months, sometimes years, of consistent work. It’s a long wait, filled with uncertainty, yet they keep showing up. That level of dedication is hard to put into words. We are lucky at Connaught that most of the nurses have pin codes.

The challenges are real. Staffing is often stretched to the limit, there are days and nights when one or two nurses are responsible for a ward with dozens of post-operative patients, each needing careful monitoring. And even when the nurses have the knowledge and the will, the tools they need are often missing or not working.

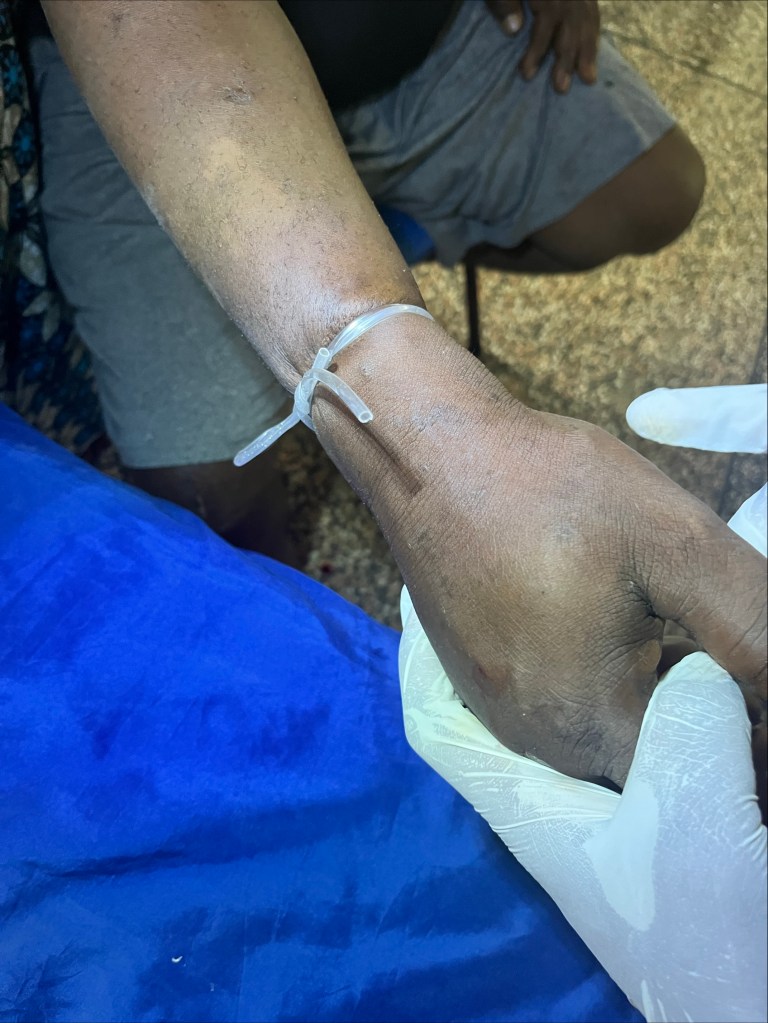

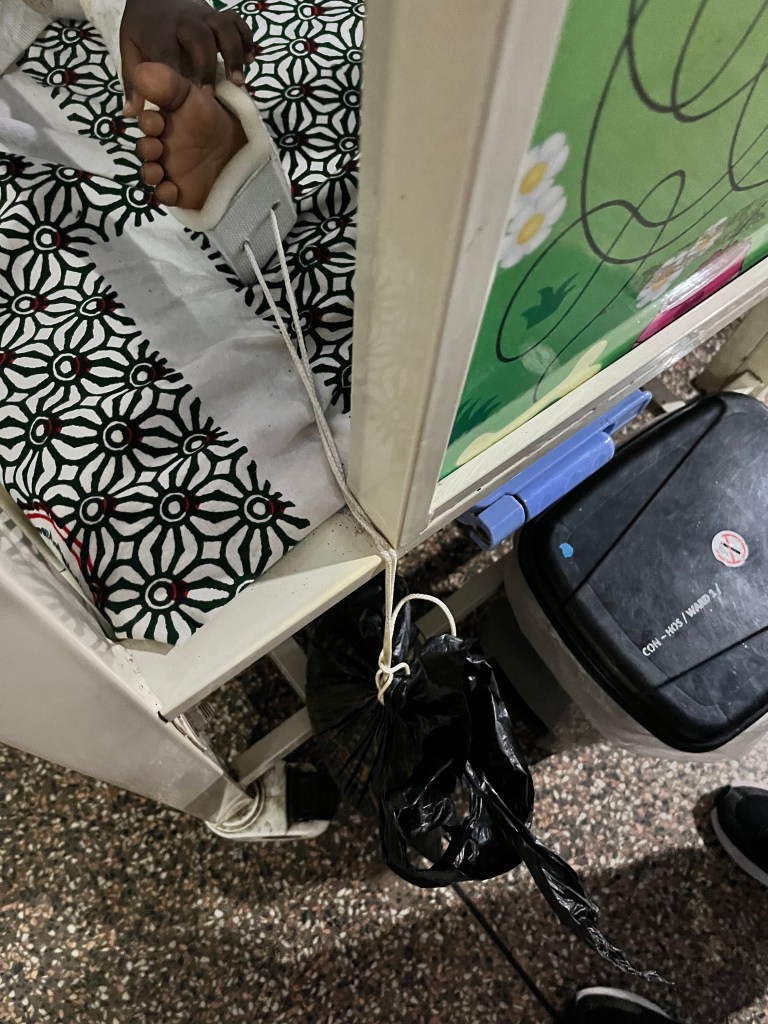

In Sierra Leone, patients are required to purchase almost everything needed for their care, from medications and IV fluids to gloves, tubing, syringes, and dressings. If a patient cannot afford these items, the nurse simply does not have the resources to provide safe or timely care.

There have been countless emergency situations where myself and other nurses have had to beg nearby patients to allow us to use their supplies for someone in crisis. Imagine pleading with one patient’s family for permission to use their IV tubing or gloves just to stabilize another patient in the next bed. Or having to make the choice between which patient gets oxygen. These are impossible choices that no nurse should ever have to make.

On the wards where I work, there is usually only one set of vital signs equipment for the entire unit. Sometimes broken, missing, or simply without batteries, and when that happens, nurses are forced to delay or skip regular checks, relying instead on observation alone. It’s not unusual to see a nurse trying to find another ward willing to lend their machine, knowing that doing so leaves those other patients without monitoring.

Oxygen supply is another constant challenge. Cylinders run out mid-shift, and concentrators, when available, can break down without warning. In emergencies, the absence of reliable equipment can be devastating.

I’ll never forget one shift when a patient began deteriorating. We needed to ventilate them urgently, but the only ambu bag on the ward was broken, it literally had holes in it. We searched the cupboards, checked the trolleys, asked other wards, but every ambu bag we found was either missing parts, had holes in it or didn’t work properly.

To make it worse the oxygen tank had ran out of oxygen and we had no epinephrine. We did everything we could, but sometimes, despite every ounce of effort, we lose patients because the tools simply aren’t there. Those are the moments that stay with you. It’s not a lack of knowledge or willingness, it’s the heartbreak of knowing exactly what to do, but not having what you need to do it.

I’m sharing this with you not for sympathy or to make you feel bad but because these are the realities the nurses at Connaught work with every day, as part of the normal rhythm of their jobs. And yet, despite these constraints, they find ways to keep going, to care for patients, and to support one another.

One story that has stayed with me, and that truly reflects the compassion and dedication of the nurses I work alongside, is that of a young man named Jose. Jose suffered from a chronic leg ulcer that required daily dressings and would eventually need a complex plastic surgery. His family, unable to afford the cost of his care, sadly abandoned him at the hospital. With no financial support, Jose was discharged and left to fend for himself.

Not long after one of the nurses found him outside the hospital, his wound badly infected. Refusing to turn their backs on him, the nurses brought Jose back to the ward. They pooled their own money to provide his food, cover the cost of his dressings, and tirelessly advocated for him to receive his surgery. Jose eventually received an amputation which although was not the original plan ended up saving his life. Jose remained on the ward for around 4 months before he was discharged recovered.

During that time, it felt like Jose became part of the ward family. Each day sitting outside the ward, he would read his Bible and greet Katie and me with the brightest smile. His resilience and faith left a deep mark on me, but even more so, it was the nurses’ unwavering care and selflessness that spoke volumes about the heart of nursing in such difficult circumstances.

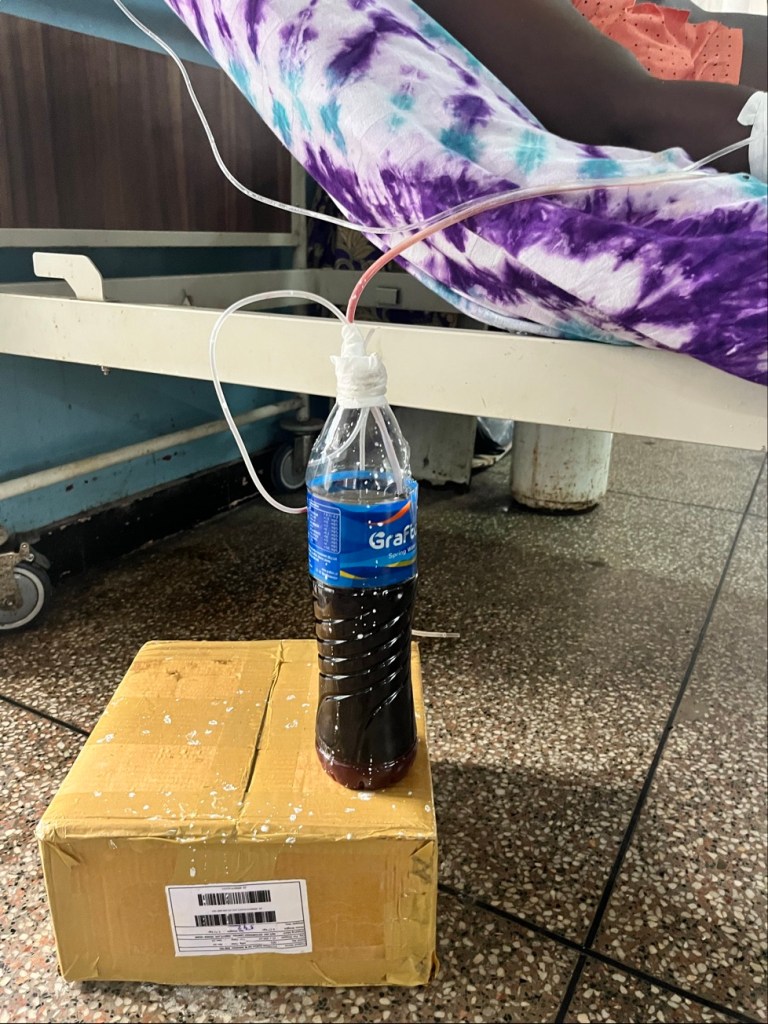

There is an extraordinary strength that runs through the nurses here. They are resourceful in ways that constantly amaze me. They think on their feet, they share what they have and they do their best to improvise solutions. Whether is making c-spine collars out of cardboard, DIY water seal chest tubes, torniquets out of old IV tubing or making home-made traction devices, I am constantly amazed by what I see and learn.

There was a day last field service when an oxygen tank on one of the wards broke during a critical moment. Back home in a hospital, you would simply switch to another oxygen bottle, or more likely, you’d have unlimited oxygen piped straight from the walls, a luxury we often take for granted. That is not the reality here at Connaught. Most wards only have two oxygen tanks and a lot of the time they are empty. But that day, the nurses didn’t waste a second. They pulled together, assessed the problem, and within minutes were using what they had, tape, tubing, and sheer determination, to make it work. And it did work. I remember standing there afterwards just marveling, not at the fix itself, but at the spirit behind it. I even took a photo of that moment, because it spoke so clearly about the heart of nursing in Sierra Leone: when the tools fail, the people don’t. They try with everything they’ve got.

Their resilience is born from living and working in a system that demands it. Many nurses grew up in the same communities they now serve. They know their patients not just as medical cases, but as neighbors, friends, even family. That connection drives them to keep going when the shifts are long and the resources are thin. And when training opportunities come along, they lean in with everything they’ve got.

This is the reality into which the Nurse Mentor Program steps. It’s why mentorship here is not just about teaching clinical skills, it’s about walking alongside nurses in their reality, helping them build confidence, leadership, and a vision for how they can influence care in their own hospitals. When you understand both the weight of the challenges and the depth of the strengths here, you start to see why this program has the potential to create change that will last for generations.

What is it We Actually Do?

So you’re probably wondering by now, what is it exactly that Katie and I do at Connaught Hospital. Together, we lead a Nurse Mentorship Program, which is part of the larger Safer Surgery Program. The heart of this program is simple but profound: every patient who comes for surgery at Connaught Hospital deserves safe, high-quality care, not just in the operating theatre, but before, during, and after their procedure. And to achieve that, it isn’t enough to provide surgery alone, we must also invest in the people who deliver the care every single day. That’s where the Nurse Mentorship Program comes in.

Our focus is on the surgical wards of Connaught Hospital, five wards in total: two male surgical wards, two female surgical ward and one pediatric surgical ward. These are busy, high-pressure environments where the needs are great and the staff-to-patient ratio is often overwhelming. Katie and I come alongside the nurses in these wards every day, not as outsiders swooping in to “teach,” but as colleagues working shoulder to shoulder. Our role is to mentor, to guide, and to support them in the delivery of surgical nursing care.

The first year of the Nurse Mentor Program was really about building trust. Before the nurse mentor program even began and before I joined Katie, she spent a lot of time at Connaught doing just that, building relationships. Walking into a hospital where resources are limited and the workload is immense, she knew she couldn’t just arrive with her own ideas and expect people to listen. So much of our early days were about forming relationships, listening, learning how the wards functioned, understanding the rhythms of care, and showing up consistently so the nurses knew we weren’t there to judge, but to walk with them. Trust doesn’t come quickly in a place where people are used to being overlooked or under-supported, but over time, by being present day after day, it grew. And once the trust was there, real mentorship could begin.

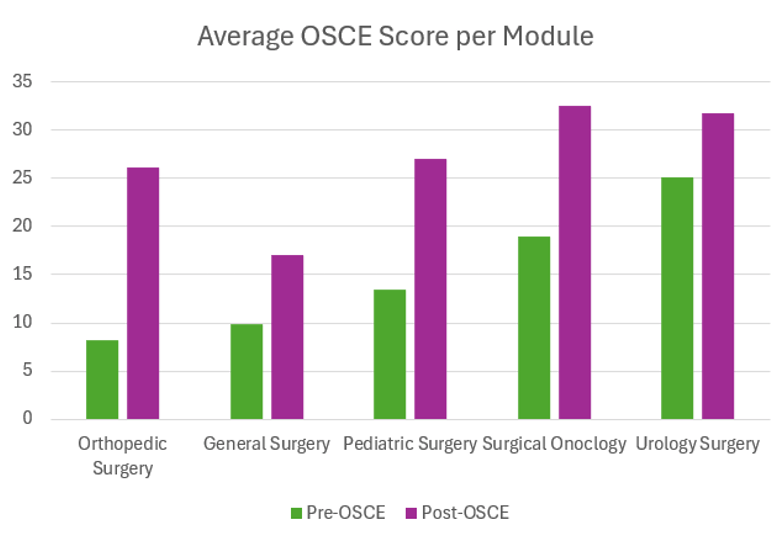

Over the course of that first year, we trained a total of 45 nurses across the five surgical wards. We created eight training modules, each one based around the surgical specialties that Connaught Hospital provides. Within those modules we also focused on basics like patient assessment, post op monitoring, pain assessment, IPC and documentation. These modules weren’t just designed in a classroom, they were built in real time, shaped by the realities we saw unfolding on the wards each day. Each module lasted about four weeks, with small groups of six to ten nurses at a time.

Mentorship in practice took many forms including class-room based learning, simulation, 1:1 hands-on mentoring, which made up the largest part of the program and some on ship mentoring. Some days it meant working alongside a nurse at the bedside, talking through an A–E assessment, helping them interpret vital signs, or guiding them through wound care. Other days it was about running simulation scenarios, which the nurses absolutely loved. Simulation gave them the chance to practice critical skills in a safe, controlled environment, without the pressure of a real patient’s life hanging in the balance. You could see their confidence grow as they worked through the scenarios, repeating them, laughing at their mistakes, learning from each other. It became a highlight of the program, because it created a space where learning felt alive and safe.

There were also theory days, where we’d step back from the wards to consolidate knowledge, and structured clinical assessments where nurses could demonstrate new skills and see their own progress. And of course, there was a lot of bedside teaching, those one-on-one moments where a mentor and mentee stand together at a patient’s side, and something just “clicks.”

But not every day looked like a lesson plan. There were days we walked into the wards and found them so full, so busy, that there was no space for formal teaching. On those days, we simply put on our hypothetical gloves, rolled up our sleeves, and worked as nurses. The most powerful mentorship isn’t about standing back and instructing, it’s about being right there in the middle of chaos, showing by example what compassionate, safe care looks like.

That first year taught us so much. It showed us not only the challenges of surgical nursing in Sierra Leone, but also the hunger for growth, the openness to learning, and the deep resilience of the nurses we walked alongside.

Time to Pause…

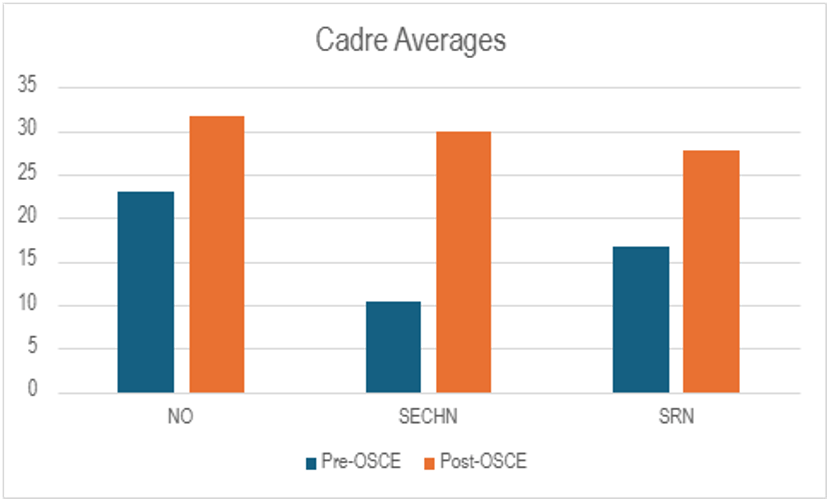

After one year of mentoring, it was time to take a pause, evaluate what we had learnt and the impact of what we had been doing. Now Year One of the Nurse Mentor Program was not without its challenges. From the very beginning, we realized just how wide the variation in skill levels was among the nurses. Some had strong foundations ( the NOs), while others were still grappling with the most basic principles of surgical nursing (SECHNs).

Designing content that engaged and supported everyone at once was not always easy. On top of that, staffing shortages at Connaught meant that nurses were often pulled in multiple directions. Many were also enrolled in university courses, which meant attendance at mentorship sessions could be low or inconsistent. And because this was a pilot initiative, there was no existing structure, no policy framework, no long-term plan for mentorship in place. We were learning as we went, building something new

And yet, despite the very real challenges of that first year, the achievements were remarkable. One of the reasons we saw progress was because the program itself was adaptable and flexible. We refined it continuously, responding to the realities of the wards and the feedback of the nurses themselves. We introduced skills assessments and logbooks so that progress could be tracked in a meaningful way.

We separated knowledge tests into general surgical care and specialty-specific knowledge, which allowed nurses to engage with material that was directly relevant to their work. And we even adapted classroom sessions, enabling more interaction, better engagement, and helping us overcome the constant staffing pressures that so often pulled nurses away.

We also saw change in the way nurses interacted with their patients. Especially those who had on-ship placements and were mentored in a different clinical environment came back with a new energy and a deeper sense of how compassionate communication can transform care. That in turn spread across the wards, lifting the overall culture of nurse-patient relationships.

Some feedback we received from nurses included:

“I learned a lot about patient communication,”

“I will continue to practice every day to maintain the process for the benefit of the patient”

“I strongly believe that the knowledge and skills that I learnt through this mentorship will change my practice”

And the results spoke for themselves. One of the ways Me and Katie assessed our nurses skills was through an A to E assessment OSCE. We assessed their baseline before mentoring and then again at the end. Before the mentoring, only 16% of nurses passed their A to E assessment; after mentoring with me and Katie, 76% passed, a transformation not just in skill, but in self-belief. Nurses themselves described the change: One nurse said “It prepared me to deliver with confidence and honor.”

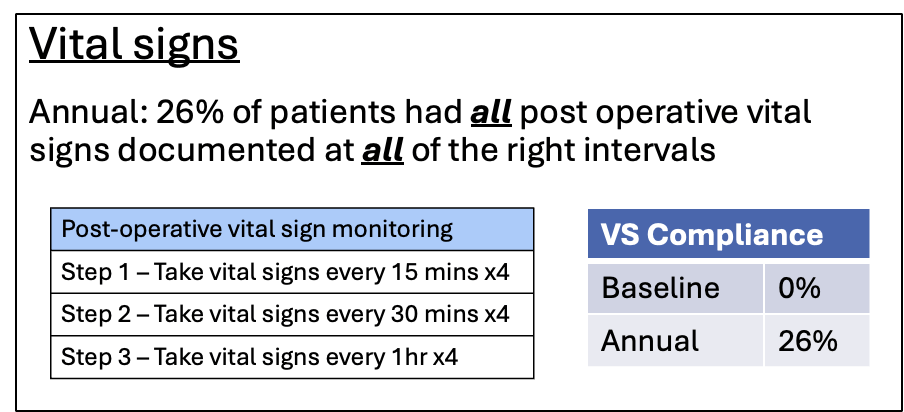

For me though I think one of the most powerful achievements came in the area of post-operative vital signs. Now for anyone that doesn’t know how often we as nurses have to take post op vitals signs its usually around every 15 mins x 4 for 1 hour, every 30 mins x 4 for 2 hours, every 1 hour x 4 for 4 hours, and then every 4 hours x 4. That’s a total of 16 sets of vitals.

When we first looked at how often vital signs were taken in the first 12 hours after surgery at Connaught, almost every patient—94% of patients—were only having their vital signs checked between zero and four times. That’s not enough for safe post-operative care. As you can see on the graph only a tiny 6% were getting them checked five to nine times, and no patients were reaching the recommended post operative vital signs monitoring. This translates to 0% of patients received post operative vital signs at the correct intervals.

Honestly, we had no idea what to expect when we did our annual data collection. But by the end of the year, 26% of patients had all post operative vital signs documented at all of the right intervals. Now, 26% might not sound impressive at first glance, but in this context, it is groundbreaking. It means that over a quarter of patients who previously would not have been monitored properly were now being assessed consistently, giving nurses the chance to catch deterioration earlier and intervene faster. In a setting where resources are limited, this improvement is a massive step forward, and it represents real lives saved. On top of that our data showed that 59% of patients were receiving vitals 10 or more times in the first 12 hours. That’s nearly a full set and a massive improvement from 0%.

So What’s Next ?

I think Year 1 showed us that when you invest in nurses, when you mentor them, and when you believe in their ability to grow, they rise to the challenge. Now, as we move into Year 2, we are building on that foundation. One of the big lessons we learned last year is that while external mentors like myself and Katie play an important role, true sustainability comes when mentorship is driven from within.

At the end of last field service in partnership with Connaught Hospital we formed a working group which comprised of Connaught Leadership, The Senior Matrons, the In-charges of the surgical wards and the Training Coordinators. We began meeting on a monthly, sometimes weekly basis to develop Year 2 of the program together. This allowed us to create a program that was locally driven and imbedded within Connaught Hospital.

So this year, we have shifted to a ward-based continuous mentorship model. We will be training 20 State Registered Nurses and Nursing Officers from the surgical wards to become clinical mentors themselves. The program adopts a strategy similar to a “Training of Trainers” approach but instead focuses on mentoring the mentors. These mentors are being equipped not only with advanced clinical knowledge, but also with skills in adult learning, bedside teaching, and giving feedback.

After an intensive five-day training back in October, the mentors returned to their wards and with the support of Katie and I, they began mentoring their colleagues as part of daily patient care. Each day we come alongside them and provide support in their mentoring whether that be a teaching session, simulation or 1:1 mentoring with their mentee.

The idea is simple: learning doesn’t happen in isolation; it happens right at the bedside. A nurse checks a wound, and her mentor is there to guide, ask questions, and model best practice. A post-operative patient needs urgent monitoring, and the mentor can coach the team in real time. Every interaction becomes a learning opportunity. And we aren’t pulling nurses away from the ward.

Each month, we introduce a new clinical topic, ten in total across the year. These topics were identified and chosen by the nurses at Connaught. We started with the basics like vital signs, A–E assessment, and documentation, and then move into more complex areas like post-operative complications, sepsis management, wound care. At the end of each topic, mentors receive certificates of completion, and when all ten are finished, we’ll celebrate together with a graduation.

This program is practical, locally driven, and designed in partnership with Connaught’s own educators and leaders. Our goal is not just to improve clinical skills, but to foster a culture of safety, teamwork, and professional growth. And we’re already seeing the excitement among the nurses stepping into these mentor roles. One of them told me, “I want to be the nurse who teaches the next nurses.” That’s the ripple effect we are aiming for.

This year is about sustainability. It’s about Connaught Hospital taking the lead with Mercy Ships standing alongside as a partner. It’s about shifting from training for the nurses, to training with the nurses, and ultimately, to them training each other.

I believe this is where the real transformation happens, not just in improved patient outcomes, but in nurses recognizing themselves as leaders, educators, and change-makers. That is the heartbeat of the Nurse Mentor Program.

What a Journey…

When I think back over the last year of working with ETA, I realize this work has taken me on an emotional journey I never could have anticipated. There have been moments of deep frustration, standing at a bedside knowing exactly what to do, but not having the tools to do it. Times when I’ve come home from Connaught with tears in my eyes, carrying the weight of patients lost, not because the nurses didn’t care or didn’t know what to do, but because oxygen ran out or equipment failed. Those moments have tested me, and at times they’ve left me asking hard questions about what “justice” in healthcare really means.

And yet, woven into that frustration has been joy, pure unfiltered joy. Joy in watching a nurse who once doubted her own ability confidently teach her colleagues. Joy in seeing a patient smile after weeks of suffering. Joy in the laughter that bubbles up in the middle of a chaotic ward when a teaching moment suddenly “clicks.” It’s in those small, ordinary victories that hope feels alive.

This journey has changed me. I came here thinking I would be the one teaching, but I’ve learned just as much, if not more from the nurses I walk alongside. They’ve taught me resilience that doesn’t quit, faith that holds steady when resources run dry, and a way of leading that isn’t about position or title but about presence, sacrifice, and community. It’s reshaped my view of global health not as outsiders bringing solutions, but as partners learning and building together.

It has also transformed the way I see nursing itself. Back home, nursing often looks like skill and knowledge wrapped in professionalism. Here, I’ve seen that at its core, nursing is about courage, the courage to keep showing up even when you aren’t paid, the courage to improvise when the tools are missing, the courage to fight for a patient who has no one else to fight for them. That kind of courage is contagious, it challenges me daily to be braver, to trust more, and to lead with humility.

There are still days when doubt creeps in, when the need feels overwhelming and progress too slow. But then I remember the faces, the nurses stepping up as mentors, the patients whose stories remind me why we do this, the glimpses of transformation that prove change is possible. And it’s in those moments that I feel proud—not of myself, but of the nurses of Sierra Leone, who embody every day what it means to be strong, compassionate, and unshakably committed.

That’s the heartbeat behind our work, and that’s why I believe in this program so deeply. Because in the end, this isn’t just about training or data points, it’s about people. It’s about choosing to hope, to invest, and to believe that even in the hardest places, light can break through.

Final Thoughts

As I close, I want to leave you with just a few final thoughts. If you take nothing else away from what I’ve shared, let it be this: investing in people changes everything. Buildings, equipment, programs, even ships may come and go, but when you equip someone with knowledge, confidence, and vision, that impact ripples outward, for patients, for families, for communities, and for an entire nation. And it lasts long after we leave.

Jesus said in John 15:16, “You did not choose me, but I chose you and appointed you so that you might go and bear fruit – fruit that will last.”

That’s what this work is all about. It’s about bearing fruit that endures – through lives transformed, through nurses empowered, through hope restored in places that once felt forgotten. That is the heartbeat of ETA: to plant seeds of change that will keep growing long after our season here is done.